Posterior Lumbar Fusion

Definition

Fusion literally translates “to join” and in spine surgery this means that two vertebrae are joined together to make one. There are many reasons why one would perform a fusion (see below) but in essence the surgeons endeavors to trick the body into thinking that the two bones to be fused are a single bone that has broken and then sets up the right conditions so that in healing the bones heal as one. Just as if you broke your arm, 2 bones with sticky ends would become one. In the arm’s case, a plaster cast is applied to hold things in place until the bones are healed, typically six weeks. In the lower back screws, plates, rods, cages and an external brace take the place of the plaster cast, and full fusion occurs after 6-12 months. The “sticky ends” in the case of the spine are the roughened surfaces of bone. Typically bone graft, usually the marrow, is taken from the hip and placed between the roughened surfaces. When bone healing occurs, new bone comes out of the roughened surfaces and migrates along the transplanted bone or BMP (see below) to bridge the area to be fused. Ironically, at 12 months all the transplanted bone has been replaced by new bone. Understanding all of the above, it becomes clear that although there are a lot of screws and hardware involved, the operation essentially joins bone to bone and it takes a full 6-12 months to heal. All fusion patients should not smoke for one month prior and three months after the surgery as the healing rate of the bone (i.e. the success of the fusion) drops from 90% to 40-50%. Similarly NSAIDs such as Celebrex or ibuprofen must not be taken for three months after surgery as they also reduce the fusion rate by 20%.

Anatomy

Looking at the anatomy section, fusions are typically done in one of three places. The typical fusion is a posterolateral fusion where bone is placed in the bony gutters between the transverse processes. This is the commonest fusion done and involves a large amount of muscle dissection. Interbody fusions involve the removal of the whole intervertebral disc and bone chips or cages are placed into the cavity. This is a fusion that is technically more demanding to perform but has a higher fusion rate and, for technical reasons, is more versatile. Facet joint fusions are usually done to supplement interbody fusions and involve the removal of the facet joint capsule and packing the joint with bone graft.

Reason For Operation

The two least controversial reasons for a lumbar fusion are for cases that involve trauma or tumor. In both of these cases, either the situation in the spine appears unstable (meaning the spine is prone to unusual movements under normal conditions which can damage tissues or cause pain or deformity) due to the underlying pathology or else the surgery required to decompress the neural structures is deemed to render the spine to unstable once this is achieved. Fusion for degenerative disease (so called “wear and tear”) is more controversial but is commonly performed. In this setting fusion can also be performed for many reasons. The commonest reason I will perform a fusion is for a spondylolisthesis. This is where one vertebrae is slipped forward in relation to another. Not only does this throw the back out of alignment (so called “sagittal balance”) but it can cause pressure on nerves, particularly when they exit through their neural foramina. A typical spondylolisthesis is shown below:

The posterior edges should be aligned but as can be seen here, L5 (the top vertebrae) is approximately 50% of its width out of alignment with the sacrum.

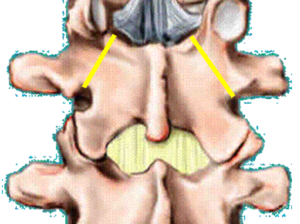

One of the more common reasons to develop a spondylolisthesis is the development of pars defects. These are shown below:

Bilateral pars defects

Pars defects occur in 6% of the population and in the vast number of cases need no intervention. When they do become symptomatic, with either leg or back symptoms, surgery is often the end result. If the degree of slippage becomes progressively worse this may require intervention as well. Degenerative spondylolisthesis is also common, most commonly occurring at the L45 level. The decision to perform a fusion in addition to a laminectomy is more complex. Lumbar fusion for ‘discogenic’ back pain is also controversial. In general, orthopedic surgeons tend to believe this entity occurs with a greater frequency than neurosurgeons who generally believe that the disc is a primary pain generator in only a few select cases. In my practice, the decision to fuse for back pain is dependent on a number of factors including the history, physical examination, MRI result and discography result.

Recent Studies have shown better outcomes in these scenarios with surgery than conservative therapy in terms of relief of back pain relief.

Technique

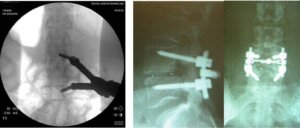

A lumbar fusion is a big operation. Screws as shown below are placed between the vertebrae that are to be fused. The bone graft or BMP is placed around these. These screws are made of titanium and usually stay in for life.

These screws are typically placed into the pedicles at each level (see anatomy). In some cases hollow cages made of a plastic called PEEK are filled with bone graft or BMP. Further bone graft is placed in front and behind the cages.

Typical cages are shown below:

A PLIF involves placement of two cages from either side of where the nerves live into the disc space ( see below).

A TLIF involves an approach from one side with one cage only that is placed diagonally and then pushed across (see below).

BMP (Bone Morphogenic Protein)

Bone morphogenic protein (BMP) is a substance commonly used when fusion surgery is done that is synthetically produced and stimulates bone growth. BMP is commonly used in all manner of fusion surgery and has reduced the incidence of fusions not taking as well as reducing the need to take bone graft from the top of the hip bone.

For years, scientists have been searching for ways to stimulate the human body to generate and repair bone more reliably and more quickly. No one appreciates the importance of such research more than the spinal surgeon. More than half of the thousands of bone fusion operations performed annually in the United States involve fusion of the spinal column. Traditionally, spinal fusion requires the transplant of bone chips from a patient’s pelvis to the spinal vertebrae to help “fuse” them together. Although this procedure can be very effective for the treatment of certain spinal disorders, the bone transplantation procedure (bone grafting) can prolong surgery, increase blood loss, increase hospital stay, increase recovery time, and increase recovery pain. Moreover, the bone grafting technique does not always reliably result in successful fusion of the vertebrae because of occasional inadequate bone growth.

Recently, scientists and spinal surgeons have demonstrated that a genetically produced protein, recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2, or rhBMP-2, has the ability to stimulate a patient’s own cells to make more bone. This finding has obvious beneficial implications for the treatment of many bone fractures and bone defects. More importantly, though, rhBMP-2 can be tremendously beneficial to patients undergoing spinal fusion. It will eliminate the need for bone transplantation from the pelvis. It may more reliably and more quickly produce fusion of spinal vertebrae. It may even reduce the need for the implantation of spinal rods and screws.

The process of stimulating bone growth within the body is known as osteoinduction. One of the pioneers in the science of osteoinduction was Dr. Marshall Urist, Professor Emeritus of the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery at the UCLA school of Medicine. More than 35 years ago, Dr. Urist discovered that the proteins that directed bone to heal itself were contained within its own matrix, or substance. It was not until 1988 that these proteins were individually identified and genetically reproduced. Thereafter, it was quickly discovered that rhBMP-2 could, by itself, direct the repair and regeneration of bone in various parts of the skeleton. In several laboratory experiments performed from 1993 to 1997, rhBMP-2 was shown to effectively stimulate bone growth along spinal vertebrae.

In 1997, rhBMP-2 was used for the first time in patients undergoing spinal fusion. In this initial clinical trial, all eleven patients who had been implanted with rhBMP-2 achieved successful fusion within six months from the time of surgery. In fact, 10 of these 11 patients had achieved their fusions within three months of surgery. Because theses patients did not require bone grafting from the pelvis, their hospital stays were shorter and their post-surgical pain was less than typically seen with the traditional bone grafting techniques. These promising initial findings are now being studied in several larger clinical trials throughout the United States.

There is little doubt that powerful biologic proteins such as rhBMP-2 will eventually help all surgical specialists treat a variety of common as well as complex spinal disorders. These osteoinductive factors will enable surgeons to modify their techniques to minimize the invasiveness of their operations. Ultimately, the goal will be reduce the pain associated with surgery and recovery, improve the effectiveness of the surgical treatments, and hasten the return of patients to productive and healthy lifestyles.

RhBMP-2 has received clearance from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for specific uses.

Risks

Lumbar fusions are big operations and the risks are much greater than simple laminectomies or discectomies. The risks are higher and the recovery is longer. Having said that the vast number of patients undergoing this operation do well. Because they are longer operations, there is more blood loss and blood transfusion is sometimes always required. A cell saver is used in surgery to reduce the need for this and bleeding is recycled with this.. The risks of nerve injury, hardware problems, infection etc. etc. are probably in the order of 2-10%. The risks of general complications are slightly higher than those for a simple laminectomy. Despite this daunting prospect, most patients do well. Typical operating time can be anywhere from 2-4 hours. Every operation is different. A bladder catheter is usually in place. The patient will usually have a button for pain control (PCA). The evening of or the day after surgery, the patient is mobilized in a lumbar brace, with the assistance of a physical therapist. Most patients note that the first few weeks after surgery is tiring and painful, but by six weeks and 12 weeks after surgery most are usually very glad they had the surgery done.

Expectations

It is difficult to look at likely success rates when the indications for surgery are quite varied. This is something that the surgeon will discuss with the patient prior to surgery. It is important to remember that with cancer or trauma there is often little choice to having surgery but in degenerative disease surgery is always a treatment option. The patient must weigh up the risks and benefits of surgery and decide if they want to have the surgery.

Recovery

My patients spend 2-5 days in hospital. They are mobilized in a lumbar brace (which is basically a support for the lower back and is worn like a girdle) every time they are out of bed for a total of three months. The back is quite sore for 1-2 weeks after surgery but this improves. At discharge all my patients do is walk. They do not bend, lift, twist or sit for prolonged periods of time. Bending and lifting are particularly bad as they can lead to screw breakage and failure of fusion. Physical therapy is not started for 12 weeks after surgery although in hospital the therapist will teach you how to get out of bed and do your daily activities. Patients return for a follow-up appointment two weeks after surgery to ensure good wound healing. It important to look after the wound. Typically I advise my patients not to rub any creams on the incision and to keep it dry. Bathing is to be avoided, as is swimming but showering is OK. It is important that the wound is allowed to heal. Any signs of redness, discharge, swelling, etc. etc. needs to be reviewed by a doctor. Follow-up with the office is usually arranged for six weeks after surgery. Repeat x-rays of the spine are done at six weeks, three months, six months, one year and two years after surgery. Typical x-rays showing realignment of the spine are shown below six.

As stated in the introduction to this section, it is important not to smoke or take NSAIDs for three months after surgery as bone healing is occurring. Good back care is the rule for life after this surgery as, and this must be stressed, the back has not been returned to normal after a fusion.

Non-Surgical Options

A lumbar fusion is not a small operation. Just as in lumbar discectomy there are non-operative options that include any or all of the following and these should be aggressively pursued to try and expedite improvement in symptoms:

Conservative therapy comprises

- Analgesia with NSAIDs (e.g. Mobic, Voltaren or Celebrex)

- Analgesia with other medications such as Tramadol

- Avoidance of bending/lifting/twisting/sitting for prolonged periods

- Physiotherapy

- Hydrotherapy (particularly if back pain is a problem)

- Perineural and intrafacet steroid and local anesthetic injections

- Possibly acupuncture

- Weight loss

- Exercise

- Bracing (controversial)

Other Points

Fusing two bones puts stress on adjacent levels and this can accelerate wear and tear at these levels. This is important as patients can develop symptoms months or years later, which may require further surgery. Redo surgery can be a very arduous in this scenario.